Reduced to despair by a mad love for the beautiful English film actress Belinda Lee, returning home one night in 1960 to his house on Viale Bruno Buozzi in Rome, Prince Filippo Orsini, assistant to the papal throne, put a moka pot on the stove to make himself a coffee. But saddened and desolate, he remembered it only when the pot exploded, covering his face with fragments of aluminum and coffee.

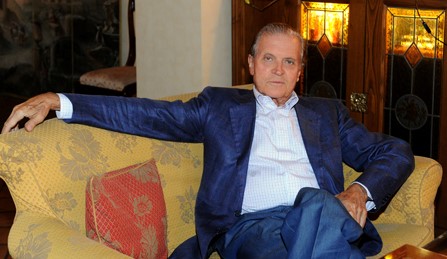

It is an unpublished episode among countless stories that have shaped the fascinating and mysterious-at least in its origins-history of the precious beverage derived from the berries of an exotic plant: precious both because it is indispensable to millions of consumers and because of the business it fuels. To illustrate how coffee is produced, processed, and consumed today, there is no better expert than someone who inherited a roasting company founded over a hundred years ago and has worked in it for more than half a century, someone who knows all its secrets: Riccardo Morganti, a name that has become a mark of quality.

Q. Morganti coffee has existed for 120 years. What is the history of this company? How was it founded? What were its origins?

Answer. It was founded by my grandfather, Romeo Morganti, who belonged to a family of apothecaries. At a certain point, because of a dispute with one of his brothers, he began to take an interest in liqueurs and at the same time in coffee; thus, assisted by his sons Giovanni, Armando, and Corrado, he started an activity in Rome producing both liqueurs and roasted coffee in a building on Via Ripetta, where I still live today. At the time, coffee came from Brazil, Central America, Asia, and Africa and landed in Genoa. From there it continued its journey to the mouth of the Tiber, and then traveled up the river on a steamboat called Garibaldi, which unloaded it at the river port of Ripa Grande, across from Porta Portese. Then it was transported to the roasting facility by carts, since trucks did not yet exist, and we even had stables for the horses. That was the beginning.

Q. And what happened afterward?

A. My grandfather died prematurely in 1915, and the three sons continued the business in the premises—by then expanded—on Via di Ripetta and in the warehouses on Via del Fiume. Around 1969 the entire plant was moved to Via di Tor Cervara, near Via Tiburtina. When the company’s move was decided, as I had graduated in architecture and we were also involved in construction, I personally oversaw the realization of the new facility. Later, due to my father’s illness, I also had to take an interest in the company’s operations, and from that moment, about 45 years ago, I have always managed it together with my cousin Massimo and with the new generation, represented by my niece Vega and my eldest son Andrea.

Q. What plans do you have for the future?

A. We are trying to expand the business, which still operates on Via di Tor Cervara, where we are building an extension, always seeking quality—the result that interests us most and sets us apart. We have always had a passion for coffee and have always lived in this environment, working mainly in the catering and hospitality sector. Coffee is consumed primarily in two different environments: in public places, especially bars, and at home. These are two distinct channels. Bar coffee focuses on quality, service, and maintenance; coffee for home use is characterized by lower quality and price, packaging aesthetics, and advertising. They are two different markets. We are also interested in the household sector, but its sales volume is marginal compared to the rest.

Q. Why is that?

A. Because coffee sales are driven by advertising and lower prices, which implies higher costs for companies, who then try to compensate with the product quality. Our company manages to remain competitive because of lower operating costs, since management has always been family-run. The difference in quality between the two markets is therefore considerable—they are two different worlds. Bar consumers prefer sweeter coffees, such as Brazilian and Central American varieties, and some Ethiopian ones. It is not true that all African coffee is inferior; some varieties are quite good, and Ethiopian coffees are highly aromatic and therefore included in higher-value blends.

Q. Who discovered coffee?

A. According to a legend dating back to the 1300s, the Arabica plant was born in Ethiopia but is also typical of Yemen, countries that in ancient times were united. Goats that ate its berries showed signs of restlessness, and the shepherds asked the monks for an explanation. The monks, making potions from the berries, realized that consuming them allowed them to stay awake longer during night prayers. When left near the fire, the berries roasted at around 170 degrees and released a pleasant aroma; the monks thus made mixtures from which the first coffee originated. The name derives from kahve, which refers to coffee both in Ethiopia—where there is a region called Caffa—and in Yemen, where Caffa is the name of a city. Another legend tells that Mohammed was struck by a sleep-inducing illness and that the Archangel Gabriel administered a brew made from black berries; Mohammed drank the beverage and recovered so vigorously that he unseated 20 horsemen and satisfied 20 maidens.

Q. How did coffee then spread throughout the world?

A. Once it became highly sought after, the Arabs spread it throughout Arabia and Asia. From Constantinople it reached Venice, where the first coffee houses arose, and then spread through Europe. During the siege of Vienna in 1529, Arabs and Turks were defeated and fled, leaving sacks of coffee under the city walls. The Austrians thought it was fodder for horses, but later learned its use from Turkish prisoners.

Q. How is it processed?

A. Processing is now entirely computerized and automated; it has changed completely since our company was founded. Today only a very small number of people are needed; employees are more involved in distribution and sales. We have adequate distribution in central Italy and for several years we have expanded abroad with good results in Czechoslovakia, Poland, Greece, Finland, and Sweden. Six years ago we acquired Caffè Camerino, which had strong distributors; we kept the Caffè Camerino brand with three “f”s in the logo. In Metro supermarkets and in the Vatican we are present with both Morganti and Camerino products; we offer Morganti as an elite coffee and Camerino as a more commercial product.

Q. What changes in your coffee when consumed at a bar versus at home?

A. The aroma changes, because at the bar it is extracted with pressure machines, whereas with the moka it is made by boiling; the first is stronger, the second sweeter. Bars use fresh coffee, beans ground on the spot, and it is certainly better; for households, the coffee is industrially ground and packaged in bags. In general, baristas do not sell coffee beans retail—at most they sell it ground—unless, besides the license for serving beverages, they also have one for selling goods; to sell packaged coffee, both licenses are required. For the Camerino brand, we have acquired several bars in Rome, for example in Largo Arenula and Piazza Irnerio, where we have kept that brand’s blends.

Q. Which areas are most suitable for cultivation?

A. The best soils are those far from the sea, free of salt, preferably in hilly areas at an altitude of 600–800 meters. For both bar and household consumption, the recipes for creating good blends of different varieties are important; Central American products, which are sweeter, combined with Indian or African ones, take on a different body and yield excellent results. We prefer to blend Brazil, South and Central America, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and a bit of Mexico. Packaged in sacks, the green beans arrive in containers and are placed in silos; the various qualities are blended and then roasted without any added aromas or other components, since in Italy all flavoring is prohibited. My company imports about 40,000 sacks of 60 kilos each annually, with different characteristics depending on their origin.

Q. How widespread is Morganti coffee in Italy?

A. In terms of bar coffee, we are not very present in northern Italy; the country is divided by regions mainly according to taste, and sometimes coffee appreciated in one region is not appreciated in another because the roasting is different. There are three degrees of roasting: in the North lighter, milder roasts are preferred; in the Center, medium roasting; in the South, stronger roasting. We have tried to expand in other parts of Italy, where we have some occasional customers; in central Italy we have a widespread, well-established presence. Elsewhere we ship the product but do not offer service. We also supply bars with machines on loan and equipment; since this service has a cost, it must be handled with special care.

Q. What does a bar need to make good coffee?

A. My answer comes down to the so-called five M’s: miscela (blend), macchina (machine), macina (grinder), mano (hand or skill), and Morganti. The moka should never be washed with detergents, the amount of coffee should be neither too little nor too much, the water should reach the level of the valve—neither above nor below; placed on a medium burner, when it starts to “gurgle,” let it finish, then turn off the heat, let it rest for 20 or 30 seconds, and then pour it into the cups. In recent years a new way of making coffee has emerged: single-portion methods. We have also adopted them, offering single portions of blends; we already did this for decaffeinated coffee, sold in 6.5-gram sachets. Generally, we supply bars with a grinder containing decaffeinated beans to keep them fresh.

Q. Which type of coffee contains the most caffeine?

A. American coffee, because it is steeped for a longer time, 5 or 10 minutes. In the moka, with the same amount of coffee, caffeine content is lower; the one with the least is espresso, because the passage of water through the coffee is immediate, rapid, with limited dilution. Its flavor is stronger, but that does not depend on caffeine, which is tasteless.

Q. How is coffee decaffeinated?

A. It is a process not carried out by us but by Verwerkaf, to whom we send our green beans. Pure coffee beans, immersed in steam, expand and release their caffeine; organic solvents found in fruits such as bananas and apricots are also used, and they cause the caffeine to be released. From this, a white powder is obtained for pharmaceutical use. In any case, caffeine does not produce the same effect on everyone; much depends on the blends. Highly refined blends contain little caffeine; cheaper coffees usually contain more. Since caffeine is tasteless and grind costs are the same, it is not clear what justifies the difference in price. The best coffees contain little caffeine.

Q. What lies ahead for the future of this beverage?

A. Single-dose coffee is spreading widely, also because it is heavily advertised; pods do not pollute and are easy to dispose of, while capsules have disposal problems, and both require special machines. We also produce Morganti pods, available at our retail points for household coffee. While the pod is universal and can be used in any machine, the capsule can be used only in some. In any case, in the future much single-portion coffee will be consumed—pods, capsules, etc.

Q. Of all the ways to make coffee, which one, in your opinion, is the best?

A. The best coffee for home use is made with the Neapolitan coffee maker, though it is no longer commonly used because the coffee would need to be ground differently and the extraction is slower. The moka has taken over, but now faces competition from single-serve machines. Personally, I prefer moka coffee: sweeter and more pleasant.

Q. What are your plans?

A. We aim to expand operations and enlarge the company; we are focused on spreading the brand while always maintaining quality. My son mainly handles international expansion. In Denmark we have a strong presence with the Camerino brand. We are approaching the United States by attending trade fairs and entering markets; it is difficult, even though Italian coffee is loved abroad.

Q. If you could go back, would you choose the same job?

A. I would do it all again. The results have even inspired me to coin the slogan: “Morganti, coffee by an author.”